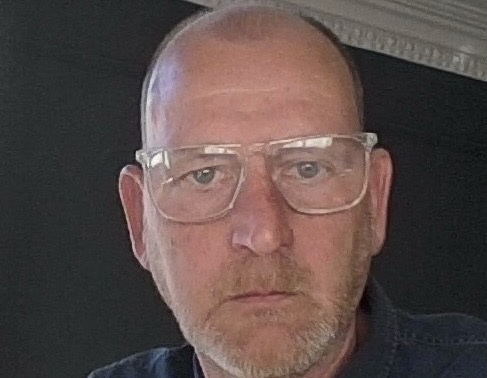

Jerry Perkins is CEO and co-founder of Wasted Talent, a UK music media publisher which was originally launched as Development Hell in 2003. He had previously been an advertising manager and publisher of music magazines at the former EMAP. Perkins and fellow EMAP colleague David Hepworth launched The Word in 2003, with The Guardian as a 29% shareholder. The magazine closed in 2012.

In 2005, the company acquired MixMag from EMAP and, in 2018, The Face and Kerrang from Bauer which itself had bought EMAP radio and magazines. Subsequently, former rock star manager Ian Flooks (whose Wasted Talent agency once represented The Clash, Talking Heads, Red Hot Chilli Peppers and U2) acquired The Guardian’s shareholding and is now chair of the £6mn-revenue, debt-free publisher which become profitable last year. Its 2022 financials had shown accumulated losses of £5.3mn.

Wasted Talent, which generates almost 60% of its revenue from content marketing (17% comes from ads and 12% events), still publishes the print magazines as quarterlies alongside its output of digital, social, podcasts, newsletters and events. The three magazine-centric brands have a claimed aggregate audience of 60mn. The audience is global but most of the revenue is from the UK. Wasted Talent employs some 40 people, half of them editorial. Perkins and Flooks together are believed to own almost 50% of the company.

| Wasted Talent Ltd £mn SnapShot | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| Revenue | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 6.9 | 5.0 |

| EBITDA | +0.13 | -0.5 | -0.7 | -2.0 | -3.8 | -0.9 |

| Headcount | 41 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 74 | 49 |

What were your earliest ambitions?

Initially, I wanted to work in the record industry or artist management. But the closest I got was selling flowers on a stall very close to one of the major labels, in London.

What was your first job in media?

My first job in media was helping some friends launch a magazine called ‘The Buzz’. There were five of us. No one got paid but I loved every second of it. I remember really looking forward to Monday mornings and hanging with some very cool people.

What did you most learn at EMAP?

EMAP had an energy and honesty that seemed unique at the time, in the heyday of magazines. We really felt we were challengers in a market that needed shaking up. The business was packed with young, clever people who thought they could take on any task and do it better, and most of the time we did. I was lucky enough to have a 10-year career there, becoming the publisher of all the music magazines including Smash Hits, Select, Q, Kerrang! Mixmag and Mojo. It was also where I met David Hepworth (creator of The Word) with whom I went on to launch the company that is now called Wasted Talent.

What was The Word?

It was the first magazine launch of our company, then known as Development Hell. Editorially, it was the best magazine that I’ve been involved with. Every sentence was beautifully crafted, and we had some of the best music and culture writers in the word as part of team. Sadly, this was at a time when print magazine sales were in decline and the record industry was going through its digital transformation – and ad pages from them all but dried-up. From that moment on, we were only interested in brands that we thought could transition to digital businesses. The first of which was Mixmag.

Where did “Wasted Talent” come from?

Wasted Talent was a very cool artist agency launched and formerly owned by my chair, Ian Flooks. The first two clients he had signed were Kraftwerk and The Clash, and he went on to represent a host of post-punk bands including U2. Wasted Talent is a name that I had always liked because of its rich heritage in music. Ian agreed that we should change the name of the company to Wasted Talent when we went on to acquire The Face and Kerrang!

What was the objective?

It was simply to transition the brands from print to digital without losing the trust and respect they enjoyed from artists and readers. When we acquired our three titles, 90% of revenues were print and 10% digital. Now it is the other way around. The brands are bigger than they have ever been, with a combined global reach of 60mn superfans every month. We knew that these brands – all launched in the 1980s – were no longer just commentators on culture, but had become an important part of culture themselves. The first thing an artist wants is recognition from their scene and, in many cases, that means endorsement by one of our brands.

What was the funding?

Our funding is largely from angel investors, many of whom are industry names who have built successful careers in UK music. The company has very little debt and, thankfully, is now profitable.

How would you describe Wasted Talent?

We’re the cool younger sibling of the old EMAP. I would like to think that we have a similar culture of creativity and honesty, where we grow our own talent and are open and great fun to work with. But what is really special about the business is, of course, the brands. They are a unique and important part of global culture. I think that one reason why the UK is so good at exporting music talent and curation around the globe is down to brands like these. We work very hard at giving artists a place in culture to grow, to create a scene and hopefully to mean something. It’s an important antidote to the ubiquitous world of music streaming.

What’s been your highlight so far?

Personally, it was when Mixmag won “Brand of the Year” at the UK Professional Publishers Association awards. It was brilliant to see our band of misfits on stage being applauded by my old school! The thing I am most proud of is bringing back The Face and restoring it to its rightful place at the top table of global fashion and culture.

What have been the milestones?

Becoming profitable during a very challenging period.

The global impact of Mixmag.

Last year, we did 40 Mixmag Labs in India and were credited with helping develop the scene there by giving local talent a global platform. Mixmag is currently doing a series of shows across Africa, and the Nairobi show last weekend was spectacular. It’s brilliant to see how a magazine created by a bunch of enthusiasts in the UK in the 1980s, is now such a recognised, loved and vital brand in dance music the world over.

What’s on your agenda for 2024-5?

The UK represents 20% of our audience but over 90% of our revenues, so there is obvious untapped potential there. Pre-covid, we had built a $4mn business in 18 months out of our New York office, so we know how to do it, and I’m very keen to get back into the US. Also, the record industry is about to go through another cycle of change. I’m not sure where it’s going to settle but I suspect that the role our brands play in developing new talent – and the trust we’ve earned with artists and super fans – will only become more important.

What are your best lessons?

- Launching and closing The Word taught me not to become so personally attached to a project, that it clouds the financial realities.

- Cash is, indeed, king.

- Embrace the fact that global culture, entertainment consumption and tech are constantly changing – whether we like it or not.

- The biggest and most successful brands in the world want to be seen as cool and relevant within culture. If you can help them achieve this, you’re in a good place.