Magazine statistics continue their depressing story: UK copy sales from the top five companies in the first half of 2013 are all down again, four of them 8-11% behind last year. US single-copy sales are down by 10%, as are eight of the 10 largest-selling titles. In Australia, all 13 weekly magazines are still sliding, by anything up to 30% year-on-year.

The reality, however, is that the word magazine (derived, appropriately, from the Arabic for ‘warehouse’) describes a widening range of publications, digital services, business models – and performance. So it is that weekly celebrity-studded magazines have been shredded by the first-hand gossip on Twitter; special interest magazines and those targeting older audiences are fairly stable; global magazine brands have retained their hold on upscale international advertising despite pressure on circulations; ‘customer’ magazines are doing well – because they are funded by retail, travel and financial sponsors;

and, in the UK, free distribution magazines are growing in readership, advertising and profitability. But many paid-for monthly women’s magazines, whose cover prices had long been ‘subsidised’ by advertising, are increasingly vulnerable. In their search for new business models, they will try for ecommerce profits. But some will eventually have to make momentous choices: to reinvent their businesses based primarily on revenues from readers OR advertising. Not both. That is the post-digital reality for many magazines, whether in hard copy or digital.

For some, the tough decision to abandon copy sales may actually be the almost inevitable result of aggressive price-cutting and retail promotions. In the UK’s retail-dominated magazine market, no fewer than 20 brands are currently displayed on news-stands in polythene bags containing multiple copies, free gifts (some claimed to be worth £32), books and supplements. And all at cover prices which have (mostly) not increased in the past five years.

These screeching promotions are helping to commoditise whole categories of magazines and undermine the market for copy sales. What does a relatively pricey “free” mascara say about the value of a magazine with which it is being given away? Which “target” readers are buying magazines without even being able to look at them first? How is a magazine brand enhanced by bagging it “three magazines for the price of one”? These blandishments are not rewards for long-term subscribers: they are the increasingly desperate incentives to buy a single copy of a magazine, in order to prop up an ABC figure – and advertising sales.

This clumsy marketing activity is the antithesis of the deep, personal reader relationships that have always characterised the most successful magazines. And which continue to be the reasons why so many readers and advertisers still love the medium.

The desperate increase-the-average-sales-anyhow tactics are not, of course, being used by the majority of magazines in the UK, one of the world’s largest news-stand markets. But they do include a clutch of the country’s largest magazine brands.

This week’s polythene-bagged wonders include: Hello!, OK!, GQ, Cosmopolitan, Marie Claire, Red, Top Gear, Company, Prima, Best, Look, Ideal Home, and In Style. Even if you disregard the potential damage to major brands, publishers cannot indefinitely market their magazines so expensively, simply in order to protect advertising rate bases. And, in the face of continuing circulation losses, brand-savvy advertisers may not be impressed by promotional activity that is as likely to drive away “real” readers as attracting them.

It prompts the question of whether some magazines would, instead, do better to abandon the economic madhouse – and switch to free distribution, so they can concentrate on advertising sales once again supported by the solid delivery of regular readership. In the UK, ‘going free’ has turned losses into profits for the London Evening Standard; and it might yet do the same for the London edition of Time Out, which abandoned its cover price last year. That approach might, similarly, revitalise some of the other magazines which have spent almost a decade expensively fighting revenue and readership losses on the UK news-stand.

A paid-to-free strategy is, however, much easier said than done because it necessitates a complete change in business model, not least in the quantity (and cost) of content. It calls for a change in almost everything the magazine does. But magazine (and newspaper) publishers do anyway need to stop salami-slicing costs and take some longer-term structural decisions in order to safeguard existing brands. If they don’t, traditional media will increasingly lose out to new-style operators – in hard copy as well as digital. And, again, the UK shows that these new publishers will not always be digital “natives”.

Sometimes they will be the smartest of the “immigrants”, reinventing media from the inside.

Take former journalist Mike Soutar, who seven years ago turned his back on a successful executive career at EMAP and IPC Media, to launch ShortList Media. Today, his two free weekly magazines – ShortList and Stylist – are the envy of Soutar’s former colleagues. They have total weekly circulations of 960,000 and are the profitable pillars of a fast-growing company with a turnover of £22m and increasingly impressive digital operations.

Soutar and his co-founder, media strategist Tim Ewington, talk media revolution:”You’re either an ‘incumbent’ or an ‘insurgent’. Incumbents are the established brands: big, powerful and capable of smashing smaller rivals into even smaller pieces. Insurgents are the small and medium-sized enterprises waiting in the wings. The insurgents lack the industrial power of the incumbents, but are more agile and capable of adapting quickly to changes in any given market, like birds darting around a lumbering elephant. And when it comes to the ever-changing world of magazine publishing, dexterity in the early days is a particular advantage.”

The ShortList CEO began his career – like so many other aspiring journalists in Scotland – as a poorly-paid editorial assistant at D.C.Thomson, the 150-year old conservative, family-owned company which confounds its critics with consistent success in newspapers, magazines, comics, investments in TV, and now in digital media.

To most Brits, this most private of media companies is publisher of legendary children’s comics Dandy and Beano. But Dundee-based D.C.Thomson is also the place where countless stars of UK journalism have cut their teeth and where budding executives have learned how success can come from small budgets and shabby offices. That’s how it was for Mike Soutar who started, aged 17, on Secrets magazine, writing old-fashioned fiction for old-fashioned women. He quickly found himself promoted successively to beauty editor and fiction editor, and then assistant pop editor on Patches, a teenage girls magazine. Next, he became pop editor of Jackie, which had become the UK’s best-selling teenage magazine soon after launch in the 1960s.

Working in a typically small, low-cost editorial team producing a bestselling UK-leading magazine from remotest Scotland was the perfect grounding for Soutar who next made the jump to London, first as a disillusioned press officer for Virgin and, then, as a junior on the pioneering magazine Smash Hits. The fortnightly had launched in 1978 and swept established music papers aside on its way to becoming the country’s fastest-growing magazine – and cornerstone of the EMAP empire which dominated UK media for most of the next 30 years.

He moved quickly through the ranks as Smash Hits and EMAP broke down the barriers of established media. By 1990, Soutar had become editor, although the magazine which had peaked at 880,000 at the end of 1988 had fallen to under 500,000. It was another big learning period in a go-go company that was then having to rejuvenate the magazines that had been the hottest things on the planet just a few years before.

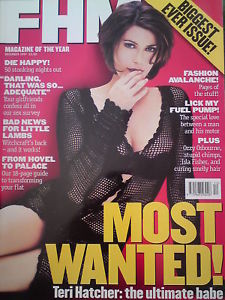

His next big break was to take over as the editor of FHM which EMAP bought in 1994, a few months after founding editor James Brown had single-handedly opened up the market for young men’s magazines with his sensational launch of Loaded for IPC.

EMAP researched the men’s market exhaustively before revamping FHM: “We spent the first three or four months just finding out about the men’s marketplace, and decided we wanted to produce a magazine that was funny, sexy and useful. We targeted the gap between GQ and Loaded – the bloke in his twenties who would still go and paint the town red with his mates, but then would have to get up the next morning and carry on with his career – and it took off, really quickly. In the first two-and-a-half years, we took the magazine from a circulation of about 50,000 to market leadership of 365,000, and three out of my last four issues sold in excess of a half a million.”

It was heady stuff but Soutar was getting restless again. In 1997, he landed the job as managing director of EMAP’s dance music radio station Kiss FM. Two years later, he was off again, flying to New York by Concorde to launch Felix Dennis’s Maxim in the US. That same year saw him involved in an abortive bid with media star Chris Evans and PR whizz Matthew Freud to acquire the tabloid Daily Star – before it was snapped up by Richard Desmond as part of the Daily Express group.

In 2000, the 34-year-old Soutar joined the longtime UK magazines leader IPC Media, then owned by Cinven private equity and chaired by his former EMAP boss David Arculus. He was successively managing director of the company’s Music & Sports division and editorial director, mainly responsible for new magazines. He successfully launched Nuts into the then booming market for men’s weeklies, followed by Pick Me Up to compete with Bauer in the quietly super-profitable puzzles and real life market. Along the way, Time Warner acquired IPC Media for a £1.2bn price tag only the sellers want to remember.

Mike Soutar was a young man in a hurry but is credited by former IPC colleagues with a careful approach to planning. ” He’s very methodical, very considered, but then implements his plans with real follow-through, power and passion. He has absolute belief in his own abilities, but he plans really carefully. He is confident, endlessly enthusiastic and totally driven. If he wants to make something happen, he will. He loves breaking new ground. His enthusiasm is infectious.”

Another says:” He gave IPC a real sense of its own potential. He brought confidence and the conviction that things could be great.” Lovely stuff for Soutar’s CV and his former boss, longtime IPC Media CEO Sylvia Auton once told colleagues: “Mike can talk the birds down out of the trees.” It didn’t last. In 2006, his departure from IPC was marked with a terse announcement and no word of thanks: “After six years with the company, group editorial director Mike Soutar has decided it is time to leave. In accordance with the terms of his contract, Mike is stepping down from the board and taking six months’ gardening leave with immediate effect.” Ouch.

It was as if the mighty IPC Media could sense the impact on the magazine market of his (as yet undecided) next move.

Soutar and Ewington together formed a consultancy called Crash Test Media, working with clients in the UK and Middle East on product launches and development in consumer

magazines. “The consultancy was our way of nurturing some very left-field, creative ideas that were probably too unorthodox for traditional media companies” says Soutar. “The first one we really focused on was the idea that eventually became Shortlist. We were interested in the power of free. We wanted to see how the ‘Metro’ business model would work with consumer magazines. It was at that point that we brought the rest of the team together.”

That core team included managing director Karl Marsden, editorial director Phil Hilton and creative director Matt Phare, all of whom had worked with Soutar variously at IPC and EMAP.

The next task was to raise the money. Soutar, Ewington and David Arculus managed – in a few short weeks – to secure £4m of investment early in 2007. Bringing together a small group of captivated private investors was an approach that the well-connected Arculus had used five years before in the launch of The Word by Soutar’s onetime EMAP mentor David Hepworth. This time, Soutar’s first employer D.C.Thomson became the largest shareholder. “I’m a Dundee boy and DC is probably the biggest firm in my hometown – having them invest in my business was wonderful.” Other backers included hedge fund manager Pierre Le Grange, French Connection founder Stephen Marx, film director Matthew Vaughn, and Arculus who became chairman.

The investors bought the Soutar-Ewington vision of a market where the once-booming lads magazines like Loaded, Maxim and FHM were no longer selling and – while there was an apparent gap for a title which targeted middle-class ABC1s – these digital natives expected high-quality content for free. The upshot was the 2007 launch of ShortList as a free weekly men’s magazine distributed every Thursday by 650 trained, motivated and unformed merchandisers at train stations and other centres across 11 major UK cities. They also subtly developed a “secret network” of 20,000 urban workplaces where the magazine is distributed – such as the Goldman Sachs staff restaurant.

ShortList magazine was an almost immediate hit with readers and, crucially, advertising agencies which backed it all the way to a 30% market share in under three years. They had found a way to tap into the affluent male market which had, seemingly, abandoned the newsstand as once-powerful paid-for titles plummeted.

ShortList Media struck gold because it captured the essence of free publishing success: free content that is ‘good enough to buy’ can guarantee an audience for advertisers.

But the real prize came with Stylist, the free weekly launched two years later for affluent 20

-40-year-old female commuters. The magazine, with content that included fashion, travel, beauty, people and careers news, was distributed every Wednesday across city centres as well as in French Connection stores, airport lounges and gyms. Like ShortList, Stylist started piling up media industry awards – and became profitable in under a year as ad agencies rushed to support the women’s magazine with a seemingly guaranteed audience.

Almost two years later, it launched Emerald Street a fashion and beauty daily email – named after its London address. The email was loosely based on the Daily Candy, a US-based global email with some 3million subscribers for whom Tim Ewington had worked as a consultant. Both are stylish, trend-setting daily bulletins. Emerald Street now has more than 90,000 regular subscribers – and a growing email database of affluent young women whom advertisers are hungry to reach.

The company has hit its stride with email media and last year launched Mr Hyde daily for young men which, among other things, recently organised National Burger Day. It now has some 50,000 regular subscribers.

Then, in May this year, ShortList Media launched Never Underdressed, described as “the first digital magazine that combines the high-gloss production values of monthly fashion magazines with the hourly speed and immediacy of the web”. The stunning site combines original photography and video with live news, galleries and features.

It’s an ambitious project to capitalise on the seismic shift of women’s fashion from hard copy and high street to online and ecommerce. ShortList is attacking this richest of magazine advertising sectors with a typically strong 14-person content team led by former editorial stars from Elle, Vogue, and Marie Claire. Never Underdressed also features plenty of embedded advertising links to ensure it can monetize a growing audience which already includes 30,000 subscribers.

Daringly, they call it “The Elle of the digital era”. But one suspects that the real target is Grazia, the Mondadori-owned weekly published in the UK by Bauer. It illustrates the way that Soutar is placing increasingly large bets to secure his company’s continuing growth. But the biggest bet still is across the Channel…

In April this year, Stylist was launched in France as a 50:50 joint venture with Groupe Marie Claire. The magazine is distributed free every Thursday across nine French cities with a target circulation of 400,000.

The Marie Claire group whose eponymous magazine is published in almost 30 countries

was impressed by Stylist’s UK success in attracting advertising from initially sceptical French and Italian fashion houses. And the Paris-based launch seeks to capitalise on the expansion of free dailies in France and, indeed, the long-term growth of the 700,000 free weekly Sport (whose less successful UK edition was once passed up by Soutar). But no informed observer of magazines or of doing business in France doubts that this is the venture that can catapult ShortList Media into the international media big time – or cut short its ambitious growth strategy. And no one can doubt either that an “unequal” partnership of a small independent company with a large, prosperous partner (in its home market) can bring disadvantages as well as advantages – if the going gets tough.

Meanwhile, ShortList Media – which is two-thirds owned by Soutar, Ewington, Arculus and D.C.Thomson – continues to make huge waves in the UK media market. Its proven skills in building – and monetizing – reader relationships in hard copy and digital are scaring to death many paid-for magazines.

Its statutory filings are, helpfully, those of an out-there company, in the long-term search for an eventual buyer to reward its founders. And the accounts make great reading. Turnover has doubled from £11.2m to £21.7m in the past four years which have seen losses of £400k in 2010 rebound to profits of £1-2m in 2013. Better still, it is easy to believe that – stripping out expensive development costs, not least in France – actual ‘as is’ operating profits for 2013 might be anything up to £4m. That would be a UK-best profit margin of 18%. Not bad for a six-year-old company.

But Soutar’s company is surprising in other ways. It directly employs 148 people – 60% more than in 2012 and double the year before that. Significantly, its 2012 salaries bill (including directors’ fees) was 31% of total turnover, compared with the 25-30% range of most of the UK’s largest magazine companies. Only Future’s UK salaries were a larger proportion of turnover – at 32%, but ShortList will be even higher in 2013.

These numbers do not detract from the success of ShortList Media. Far from it. This, after all, is a small, high-quality company that needs the human ‘bandwidth’ from which to grow. The potential is underlined by the experience (and continuity) of the Soutar-Ewington-Marsden-Hilton-Phare management team which is bursting with ideas. But the statistics reveal that, when it comes to employees, this new-wave company – with average revenues of less than £150k per head is much more traditional in its approach to staffing than, for example, the clutch of London-based digital businesses (like AOL and Gumtree) on £1m per head.

Perhaps that poses some questions about Soutar’s ability to sustain the profit growth. It also, though, raises the possibility that the next wave of magazine winners might just be more “virtual” than ShortList. It is clear that the contrast between, say, the free London financial newspaper City AM (employing a mere 50 people) and other dailies (employing hundreds more) is much sharper than that of ShortList versus traditional magazine publishers. Only time will tell if the disparity is significant.

Either way and above all else, though, the ShortList story underlines the huge challenges facing many traditional magazine brands, saddled with the full-cost baggage of incumbency and the fear of losing the readers and advertising they still have.

Mike Soutar must smile every time he passes a London news-stand bulging with polythene-bagged magazines and special offers from his former employers. It’s just a matter of which sectors might next be ready for the ShortList treatment. And, if Stylist takes off in France, perhaps it can become the next global magazine franchise, alongside the venerable Vogue, Elle, Marie Claire, and Cosmopolitan.

Now, that’s a prospect to rattle the cages of traditional media everywhere.

UPDATE 14 May 2015 :

Dundee-based publisher DC Thomson is to buy 100% of ShortList Media. The family-owned Scottish firm, was a founder investor in ShortList in 2007, alongside a group of financial investors and the management team. It began with five staff and now employs 150. Shortlist CEO Mike Soutar said: “DC Thomson’s acquisition is an important milestone for our business. It marks the moment where we move from a plucky upstart into a long-term growth business with the solid ownership and backing of one of the most revered players in media. Until now we have relied upon our own resources to develop and launch new brands and lines – but with DC Thomson’s investment and support we can now accelerate our launch and acquisition plans.” (source: www.pressgazette.co.uk)

UPDATE 24 May 2016:

ShortList and Stylist owner appoints as CEO Ella Dolphin (commercial director at Hearst UK, and former publisher of Grazia UK at Bauer). Mike Soutar, current CEO and founder of ShortList Media becomes Chairman.

UPDATE 26 May 2016 (The Guardian):

If you live in one of London’s hipper areas or commute into its centre, you may have been approached this morning at the tube station by a young person in a blue T-shirt handing out yet another free magazine.Aimed at the almost mythical millennial the media is obsessed with, Swipe magazine aims to stand out from Time Out or Shortlist by offering “the best of the internet in print”. Swipe’s editors say they will sift through that morass of content, decide which bits its target audience will like, then shove it in their face on their commute. They are paying a not exactly generous 10p per word to writers, but the 70-odd contributing sites get promotion for their work.

It has an initial distribution of 20,000 copies, 17,000 by hand and the rest placed in coffee shops and other millennial-friendly hubs. Publisher Tom Rendell insists that outside a media bubble of super-engaged web users, there is demand for a print roundup that filters social media. “The internet is 4.5bn pages,” he said. “It’s completely dominated by huge sites high in Google search rankings. We’re not picking the most popular or the weirdest – we are looking at this with a journalistic background and thinking how we can give the best experience.” (www.theguardian.com)