Traditional media is rightly obsessed with “millennials”, the 18-34 year-olds who have grown up with the internet. They are up to one-third of the population of most of the major economies, and are the largest, ethnically and racially most diverse generation ever. They are already some 50% of the working population of many countries and, in a decade or so, will be 75% of the global workforce. Three quarters of millennials (or “digital natives”) own a smartphone, and they know about the world largely through the internet and social media. They are, to say the least, less attached to traditional print and broadcast media than their “baby boomer” parents. While Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn have increasingly become trusted news sources, traditional journalism has struggled to engage young people. Sky News recently revealed that only 18% of 16-24-year-olds in the UK trusted mainstream media to provide them with relevant information. It’s a media generation gap which is threatening to swallow up decades of newspapers, magazines and broadcast channels.

Almost everything about millennials is enough to scare traditional media. Take this list of their views published recently by Forbes magazine:

- Mistrust advertising which they regard as “all spin and not authentic”

- Trust blogs for authenticity over some mainstream media

- Want to engage with brands on social media. Information not “spin”

- Want to co-create products with companies

- Expect brands to give back to society

So, that’s a pretty big black mark against conventional advertising, and clear signs of why native ads can be effective.

The big difference is, of course, the technology which is integrated into everything millennials do. After decades of saying “content is king”, media bosses are having to get their heads round the idea that how news, information and entertainment is delivered can be just as important as what. Millennials could not be more different to the baby boomers who built the current media industry during 50 years of revenue boom – before the web pushed the walls down.

Shift in media power

Last month, Barack Obama marked his annual ‘State of the Union’ address by giving White House interviews to prominent YouTube vloggers. Like the US President’s four-year participation in video chats on YouTube and via Google+ Hangouts, the interviews conveyed an unmistakeable message about the shift in media power.

It all adds to the frustration of traditional media at its apparent inability to conquer the fast-growing young audiences that they and their advertisers are most desperate to reach. That frustration keeps spilling over into claims that, somehow, this fast-growing “new” generation is simply not interested in news and information. But they could not be more wrong.

Millennials are actually huge consumers of media – just differently. Deloitte recently forecast an average spend of $750 per millennial in the US, including pay TV and online video and music streaming. They are fuelling the growth of Netflix, Spotify and targeted digital news operators.

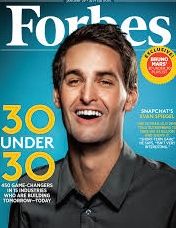

More than half of all web-browsing millennials in the US visited BuzzFeed in October, according to ComScore stats reported by Digiday. And they accounted for 61% of Vice’s 25m news visitors during the same period. The four-year-old Mic was launched “because young people deserve a news destination that offers quality coverage tailored to them” and has rushed to 19m monthly uniques. Elite Daily, the news site which was launched three years ago as a WordPress blog and now claims more than 30m monthly uniques, was last week acquired by the UK’s Daily Mail group for a reported $50m. And Snapchat’s Discover pitches the highly-popular app to become another major news source for the smartphone generation.

Generation gap

BuzzFeed was a pioneer but distinctive millennial news services are now so much broader and deeper. And it’s not just news tastes that are different. A US report this month said that only 40% of millennials tune in to live TV each month. The disparity between millennials’ perceptions of traditional and native channels is reinforced by the US-based Intelligence Group’s Cassandra Report which showed that 77% of 3,000 millennials across 10 countries said it was “important” to be informed about current affairs, but 60% said they depended on social media. A handful of traditional news media seem to have cracked it. The Economist’s boss regaled media people at a US conference recently with the claim that 40% of his influential audience are millennials.

For most, though, it really is a tale of two media worlds and of a widening generation gap. And much traditional media seems to be getting it so wrong. The reasons are not difficult to find.

Flashes & Flames calculates that the leaders of the world’s 39 leading media groups have an average age of 57 years. The five largest groups are led by men who average 72. This list includes the 91-year-old Sumner Redstone at the top of Viacom and 83-year-old Rupert Murdoch astride 21st Century Fox/ News Corp. Their respective deputies, Philippe Dauman and Chase Carey, are both 60.

Only one of the top 20 media owners has a leader under 50 – the 49-year-old Thomas Rabe of Bertlesmann. Only one of 39 groups has a leader under 40 – magazine heiress Yvonne Bauer(34) who four years ago succeeded her 72-year-old father. (There are precious few women at the top of media, but that’s another story). It is impossible not to draw the conclusion that, all over the media, 50 is considered young, evidenced by the ‘new’ generation bosses of Hearst (52), Reed Elsevier (51), Pearson (52), Lagardere (53), Axel Springer (52), Sony (54), New York Times (57), Schibsted (52), Thomson Reuters (54), and Britain’s ITV (50).

Digital difference

The contrast with digital companies could not be greater. The average age of the leaders of the 16 largest digital groups is 40 – ranging from the 24-year-old bosses of SnapChat and Elite Daily to the 54-year-olds Tim Cook of Apple and Reed Hastings of Netflix, and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos (51). No fewer than 9 digital leaders are under 40, and most are in their 30s and 40s.

It is striking that the major TV-film groups are dominated by even older men: the top 5 average 72 years. Magazine groups tend to be younger. But the challenging world of newspapers might wonder whether its powers of reinvention are constrained by the age of its leaders. In the UK, daily and regional newspapers have leaders aged 49-65. Across Europe, the average age of newspaper bosses is 59 years.

So, the leaders of traditional media groups are , on average, almost 50% (and some 20 years) older than their digital competitors – and almost double the age of their oldest millennial readers/viewers. It’s a clear picture of long-established companies fighting to win audiences from an age group to which many of their own senior executives are scarcely able to relate.

Age does not, of course, define everything about the skills and attitudes of individuals or companies. It does not really have to matter very much. But this across-the-board imbalance identifies the handicaps that many companies may suffer in their competition with digital media, namely that their people, power, language and culture overwhelmingly flow from traditional profit centres – not from the future. Is it any wonder that a company like Bauer (despite its millennial boss) describes its digital editions as “brand extensions” of print magazines? Future-focused media companies need to be able to think and act young. Clearly, easier said than done.

For all their investment in digital media, many newspaper-centric companies, for example, are tellingly dominated by people with a lifetime in print. This tends to ensure a fairly typical domination of teams by journalists and advertising sales people. By contrast, digital-only companies tend to be dominated by engineers and software savvy people: the style and manner of delivery comes ahead of actual content in corporate hierarchies and cost rankings. And, of course, digital operators know best about native advertising.

That distinction in staffing and skills influences the whole character of digital-only companies. You only have to reflect on the creativity of low-hierarchy ‘new media’ firms which allow employees to take unlimited vacations or have all their meals, leisure and even sleep-time in the office, to appreciate that. Firms which pay for their employees’ laundry, travel, home cleaning, childcare, rental cars, in-house concerts, and weekend breaks, are doing things very differently.

But this is not charity. Looking after enthusiastic ambitious young people at work encourages them to stay longer, work harder and be more committed. Money spent on perks, especially on healthy eating, could be more “productive” than the equivalent spend on higher salaries and pension plans. It’s much more than gym membership and staff restaurants. And you suspect that many starting-out millennial employees like their fun-to-funky offices more than their homes.

Most traditional companies – with relatively higher levels of staff cost and benefits geared to traditional economics and older workers – are simply unable to compete for recruits rushing to join digital startups. These are the young people joining young companies and targeting young audiences who are making it so difficult for mainstream media to catch up.

Media corporates must worry too about research into the ages of peak performance for business leaders. Harvard Business Review recently noted that the average age of those on its list of “100 best-performing CEOs” was 58 and the youngest was 46 (Simon Wolfson of UK retailer Next). Noting that inventions and scientific research have forever been dominated by people in their 20s and 30s – apparently the years of peak performance – HBR pointedly asked the question: “Could the best CEOs be too old to innovate?”

At a time when the world of media, information and entertainment is changing exponentially, it is reasonable to ask whether traditional groups are missing the beat. They need, at least partly, to mirror the audiences they are trying hardest to attract, and – at the very least – that means employing increasing numbers of young people and pushing them to the very top. Media owners need to attract millennials inside and out.

Time for reinvention

But it’s not all bad news. There continue to be plenty of highly profitable magazines and newspapers which have successfully found digital ways to capitalise on their traditional strengths. Sometimes, even a dip in profitability reflects only the need to reinvent a business model because of lost advertising with readership largely intact. However, companies need, ultimately, to be able to compete toe-to-toe with their rivals whoever they are.

The whole subject of the age difference of fast-moving digital companies adds spice to the debate about how traditional media companies can develop their future, while defending a still-profitable past. Professor Clark Gilbert’s successful twin-track strategy in managing traditional media separately from digital is based on his premise that it represents the best way to maximise the results both from old and new: two quite separate groups joined only by a common ownership. His inspired strategy for the Mormon church-owned Deseret Media group in Utah still has many more admirers than imitators. But the battle for millennial employees and customers ought to add some urgency to the agenda.

While there are a myriad of ways in which companies compete successfully, we should expect “mature” media groups increasingly to ring-fence digital-only investments from traditional media. Some may be as bold as Clark Gilbert’s Deseret, but many more will morph from large centralised groups to constellations of semi-independent companies able to compete freely and with each other – and to learn the lessons from the digital independents who are currently making all the running.

That new model should still involve established media businesses pushing into digital. But, crucially, it should also include separate, distinctive digital-only operations, led by the kinds of people with the radical types of operations that are winning millennial audiences everywhere: digital natives. These operations need to be ‘un-corporate’ and not to over-estimate the value of traditional content and brands. These future-focused media groups need to compete widely, to place many bets, and to be flexible. They also need to be tech companies as much as media.

But such get-radical traditional groups must avoid being too single-minded about what will succeed long-term in the churning media market. Innovation has always been about constant adventure and driving up the ‘strike rate’ of new product development through experience. Media groups need also to be sceptical about the advantages of corporate scale. They must exploit market opportunities in the same fearless ways as digital natives and, for many, that will only be practical in a structure which manages such adventurism separately from mature businesses.

Three of the world’s older media groups – America’s Hearst Corp, Axel Springer from Germany, and the UK’s Daily Mail group (DMGT) give some indication of moves towards this. They all once generated profits primarily from daily newspapers. But, now, they have impressively invested in digital media while (mostly) keeping them separate. Hearst for 24 years has earned more than half of its profit from a 20% shareholding in ESPN sports TV, is the world’s largest magazines group and is growing fast in B2B media. It has also been investing in BuzzFeed, Refinery29 e-commerce, Roku media player, and retail marketing platform Swirl. We might expect to see signs of it adapting this venture capital activity in order to own or control more digital companies for the long-term.

Trad media awakes

That is, more or less, the pattern of Berlin-based Axel Springer whose powering global online classifieds were kick-started with private equity participation and whose highly-profitable Bild is still Europe’s most successful daily newspaper. Today, this most digital of newspaper-centric groups earns more than 60% of its profits online. It is also investing (alongside Amazon’s Jeff Bezos) in Business Insider, and also in digital news media Ozy, and Blendle, described variously as “iTunes for journalism”.

DMGT, whose founder invented the popular newspaper more than 100 years ago, has similarly pushed strongly into B2B digital media and events. Then has come its impressive expansion in online news, and now acquisition of Elite Daily. The millennials’ US favourite has managed to build an audience of 74m readers with a team of just 65. For all DMGT’s famously light-touch management, MailOnline staffing is many times that on a scale that more resembles its newspapers than a digital native. Which will change?

There’s a long way for traditional media to go. Their young competitors are a potent reminder of the scale of media revolution now underway. Take it seriously or else.

Flashes & Flames Hearst Corp DMGT Axel Springer Deseret Media Vice News Elite Daily Mic BuzzFeed

Hi Colin I usually love your stuff but this is very thin. Seems like a light-weight filler…BUT I love qualifying as young in your definition!