Warnings that “robots are coming to take your jobs” used to conjure up images of fully-automated assembly lines and metal workers toiling on construction sites. But recent developments in AI have hinted at a potentially greater possibility of humans being replaced in an area once expected to be humanity’s last bastion – the creative industries.

These leaps forward in traditionally human areas are epitomised by two consumer-facing services built by a company called OpenAI, run by renowned (at the venerable age of 37) tech entrepreneur Sam Altman, and counting Elon Musk among its founders.

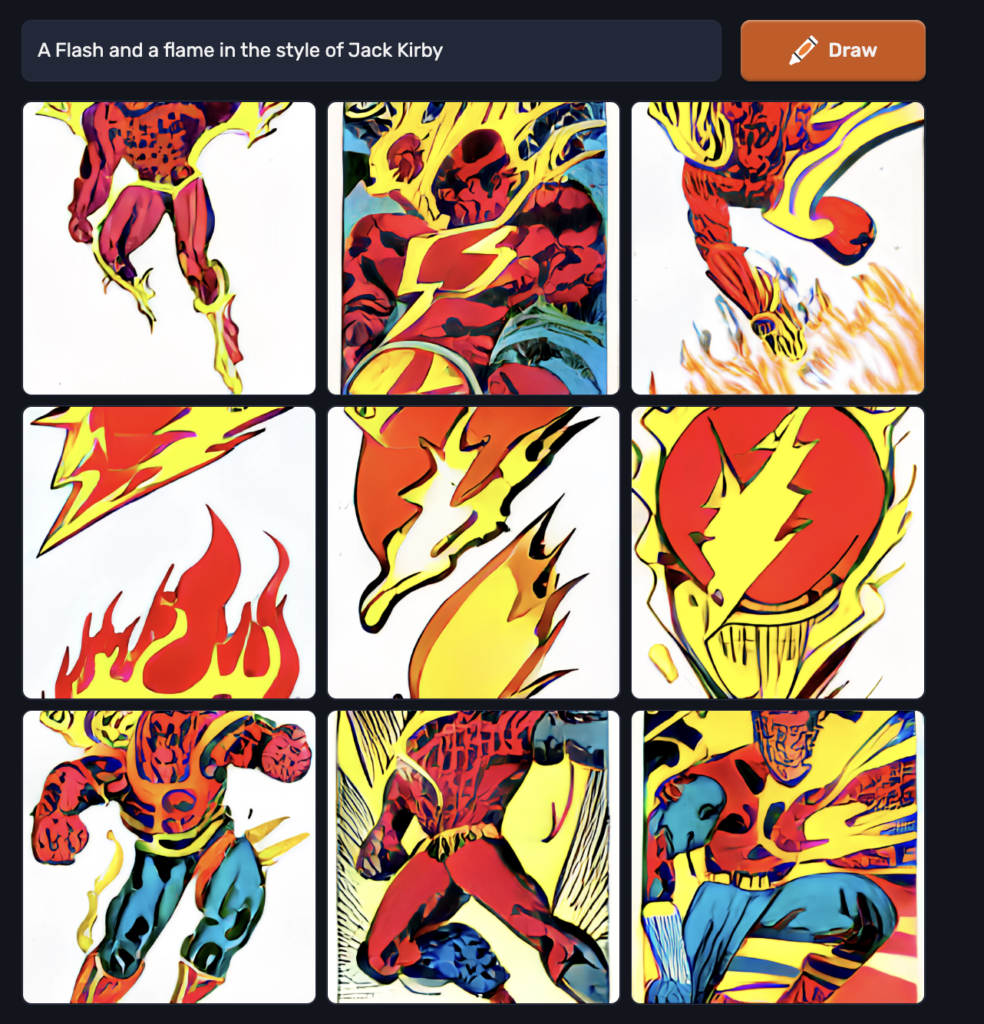

The first to really sweep the internet was Dall-e an image generator that can come up with images based on simple prompts, combining both subjects and styles, as you can see below:

Dall-e’s images are often more miss than hit, regularly producing quite disturbing combinations that don’t quite manage to get out of the uncanny valley where the not-quite-successful attempt to mimic humanity falls uncomfortably short.

However, the other breakthrough to capture attention in this area has been in text in the form ChatGPT. Unlike Dall-E, ChatGPT regularly gets very close to reproducing human-sounding output in quite a few situations, particularly when asked very simple questions.

So are the robots really coming for the jobs of those working in the media business? Not quite.

ChatGPT and Dalle-e both use the same underlying language processing model, GPT3, which enables the two systems to create outputs based on written prompts. GPT3 – as with almost all things purporting to be AI – is actually based on machine learning rather than the concept of intelligence as humans experience and use it. Machine learning effectively boils down to feeding a computer program a huge amount of data – in these instances huge amounts of text and images drawn mostly from the web – so that it learns to identify what people are likely referring to when they use various combinations of words, and can then create an output that matches them.

A key thing here is that the outputs of these systems aren’t really something completely new, but rather a best guess mishmash of the building blocks of existing content based on what it thinks someone wants to see or read. You might argue that human beings actually do something similar, but right now the human creative process still at least looks like it operates on a completely different and more advanced level.

That means that – for the moment at least – the output of ChatGPT, for instance, can come very close to sounding like the kind of polished article you might read in a newspaper or magazine, but it generally falls slightly short of what a professional journalist or writer can produce in terms of elegance.

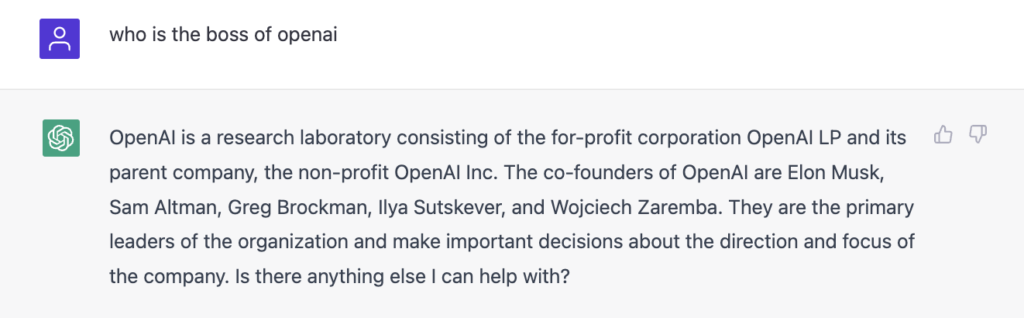

And that isn’t even the main reason that these models are still a long way from replacing journalism. Their biggest failing is actually around something you might expect a cold blooded computer to be better at – facts.

“ChatGPT as it stands today can write clear and comprehensible copy – but it struggles with consistency and factual accuracy,” says James Ball, author of The System, about the underpinnings of the internet, and also my own boss at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. “That should mean that journalists don’t have too much to worry about right now, and for high-level ad copy, humans probably still have the edge.”

One particular issue is that ChatGPT appears often to be quite significantly out of date. Here, for instance, is its answer to who owns Twitter.

As you can see, Elon Musk is nowhere to be found. Now, perhaps OpenAI’s teaming-up with Bing, the search engine owned by one of its biggest investors, might conceivably lead to better real time incorporation of new information. But, even then, a model relying on the existing web for its information is not going to be able to find out new information to fill the news pages.

There are, however, other functions within the media industry that GPTChat, Dall-e and language processing models are likely to have an influence on pretty quickly, says Ball.

“[ChatGPT] is definitely capable of turning a few key bullet points into plausible website or marketing copy, and so I would expect to see it used in these areas quite rapidly – so it could easily start displacing human workers.”

“That risk is especially acute for places that use illustration in bulk. Higher-end sites, on the other hand, want to be able to commission very particular tweaks and edits, which will still require human illustrators.

“But sites looking simply to save on a photo or image budget will find what AI models today can produce is more than satisfactory.”

It’s pretty easy to test this out for yourself. Here’s me asking ChatGPT to write a subscription renewal email.

And ChatGPT can also be used to write simple code that could automate the creation of multiple tailored marketing messages, and send them. There are, of course, solutions out there that do much of this already, both in-house and third-party, but ChatGPT looks set to quickly expand those capabilities and, quite possibly, do a lot of the work still done by marketing professionals rather than machines.

The key thing here is that ChatGPT and other language models look set to have far more impact on the back-end processes that support and monetise the content media companies produce, rather than the content itself. In that respect, they have a lot in common with preceding innovations in digital.

So, we might expect ChatGPT, or at the very least something similar, to become part of the marketing department’s toolkit, if not a competitor for the team itself. But, anyone who’s churning out simple photoshop illustrations or very basic stock photography, might have reasons to be worried.

For everyone else, these new models will still have an impact. But – right now – they all look like tools that will help media people do their jobs not take them.