New York is the home of many of the world’s largest magazine publishers and also of some of the best-known city magazines. The 90-year-old New Yorker is a magazine of commentary, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry, whose writers have included many of the most respected authors of the twentieth century. The 60-year-old Village Voice, launched by Norman Mailer in 1955, was a prominent “alternative” voice in the protest years of the 1960s and 1970s. The appeal of both extends well beyond New York. That’s how it is also for New York magazine, which was launched in 1968 as a brasher, less polite and less wordy weekly rival to New Yorker. Its mix

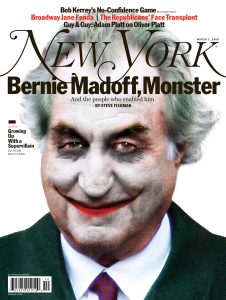

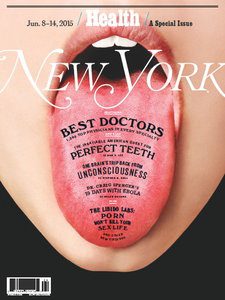

of photography and good writing about politics, the arts, fashion and food has a readership that is 36% outside New York City. The magazine does “best doctors” and “cheap eats” and has profiled everyone from Bernie Madoff to Steve Jobs, Yoko Ono to Amal Clooney, and Hillary Clinton to Madonna. It tells its readers “How to Be Happy”, “How FIFA was Screwed Once America got interested in Soccer”, “How to End Racism in Schools”, and about “The Secret Lives of Married Men.”

Award winner

It publishes special issues on health, fashion and design. And, every year, there’s a collectable Yesteryear edition on some aspect of the city’s history. This magazine has more confidence and creativity than a whole rack of the world’s city publications. That’s why it wins more awards than all others in the US – and merits the attention of publishers everywhere who are fighting for the future of print media.

It was the brainchild of legendary US editor Clay Felker, first as a supplement to the former New York Herald Tribune in 1964 and then, when that newspaper folded four years later, as an independent magazine.

Felker and graphic designer Milton Glaser (the man who created New York City’s much-imitated I ♥ NY logo) produced a magazine to compete for consumer attention in pre-internet times when television threatened to overwhelm print. It was a distinctive combination of long narrative articles and short, witty ones on consumer services. The headlines were bold and the graphics even bolder.

Felker almost invented the “New Journalism”, using the techniques of fiction to make reportage more dramatic. It was exemplified by his star writer Tom Wolfe, and it was no accident that several New York cover stories spawned successful movies. Felker’s trail-blazing magazine adopted a tone that was unapologetically elitist and trendy.

The emphasis on business and culture was pure New York. But it was entertainingly obsessed with the rich and powerful and what its creator described as “the high jinks of wise guys”. Journalist’s son Felker was the perfectly-tailored New York insider who lived the life,

but was actually from Missouri in the US mid-west. Like Scott Fitzgerald’s fictional Jay Gatsby, he never quite lost the outsider’s sense of wonder at the glamorous outspoken city to which he had moved in his 20s. Newsweek magazine once described Felker as having “a Gatsbyesque drive, a zest for power and an uncanny knack for riding the trendy currents of Manhattan chic.”

Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, Gloria Steinem, Nora Ephron, Pete Hamill, Ken Auletta, and Gail Sheehy were among the writers who made themselves and the magazine famous. But Felker never forgot the ‘bread and butter’ coverage of where to eat, shop, drink and live that kept readers hooked. For New Yorkers and those who admired the city from afar, the magazine – like the Big Apple symbol that symbolised it – perfectly captured the city’s energy and excitement. Its ubiquitous infographics and inventive typography were way ahead of their time.

The magazine also became known for its competitions and cryptic crossword puzzles which, initially, were compiled by the composer Stephen Sondheim, no less. Woody Allen also wrote for the early editions, which captured the imagination of advertisers as well as readers. The first issue on April 1, 1968 had 64 pages of upmarket ads from the likes of Tiffany and Bergdorf Goodman. Time magazine, in its one-time role above the fray of mere media mortals, applauded the debutante for “capturing the excitement of the city in a way few other publications have.”

Radical chic

It was an auspicious start for the magazine which reported on a 1970 “radical chic” benefit party for the revolutionary Black Panthers, held in Leonard Bernstein’s Park Avenue penthouse, that seemed to capture New York’s culture-clash ethos. Two years later, it spun-out a feminist section which became Gloria Steinem’s pioneering Ms. magazine.

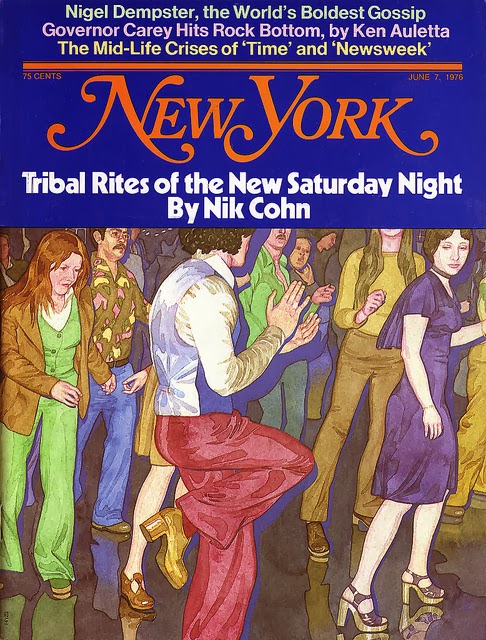

In the 1970s, as New York City wrestled with the threat of bankruptcy, the upbeat magazine was full of the deals and deeds of Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal. When it ridiculed President Ford on the cover as Bozo the Clown, political commentators said he never recovered. And its 1976 story, “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night”- about a young man in a working-class Brooklyn neighborhood who, once a week, went to a local disco – became the movie blockbuster “Saturday Night Fever”. It made John Travolta into a superstar but, years later, journalist Nik Cohn admitted that he’d done no more than drive by the door of Brooklyn’s Odyssey disco. He made the rest up, having originally been sent to report on nothing more than dance competitions.

A 2008 Felker obituary attempted to explain the success: “The brilliant germ of this magazine, when Felker launched it in 1968, wasn’t the duh geographical idea, covering a particular set of Zip Codes stylishly and colorfully on glossy paper. Rather, New York’s central subject has always been our local pageant of ambition, the yearning and hustling and jostling for power and—even more—status.”

In 1977, the magazine itself made the news when it (and the Village Voice which Felker had acquired in 1974) was bought by Rupert Murdoch after a fierce fight with Felker, whom he had befriended several years before. The editor-founder was neither the first nor the last to be charmed by the Aussie entrepreneur’s life story of an outsider motivated by the need to rebuild his father’s lost newspaper empire in small-town Adelaide.

The scuttle-butt of what happened next was made for New York magazine: at lunch together, Felker was railing against Alan Patricof, the founder of Apax private equity which owned a controlling share of “his” magazine. Murdoch reportedly sensed an opportunity, rang Patricof and arranged to buy his shares without telling Felker, who later spat: “Rupert Murdoch and I disagree on the meaning of friendship, of human values and the meaning of journalism.”

Some 40 of the magazine’s employees – who, for the previous year, had watched horrified as Murdoch had brought his racy tabloid skills to bear on the newly-acquired New York Post – resigned in protest. The first thing Murdoch did was to veto a planned feature about himself. Time magazine marked the takeover with a cover story featuring the Aussie entrepreneur as King Kong seizing media properties as he climbed skyscrapers.

Murdoch sells

New York magazine’s spirit survived the loss of its founder-editor, and had its most profitable decade in the 1980s. But, in 1991, Murdoch’s News Corp was forced to offload its magazines, after being almost drowned by debt. They were bought by Primedia and New York magazine showed it had not lost its touch when, in 1992, it published one of the first big stories on presidential hopeful Bill Clinton at a time when few people had even heard of him. But editors came and went amid stories of the magazine’s poor financial performance. And it was sold again in 2003 – to Bruce Wasserstein, who trumped a well-publicised field of media suitors with a last-minute cash bid of $55m, reportedly besting New York Daily News owner Mort Zuckerman by a cool $10m.

The Wall Street investment banker once claimed to have worked on more than 1,000 M&A deals. He had coined the phrase “Pac-Man defence” used by target companies fighting the hostile takeovers with which he made his name. His “Bid ‘Em Up Bruce” reputation briefly alarmed his new employees. But they soon realised that there was another side to the man who, as chairman and CEO, floated the Lazards investment bank in 2005.

The Brooklyn-born banker was a sometime writer (of four books) whose grandfather was a playwright, as was his Pulitzer prize-winning sister. Journalism was described as a first and lasting love which he had once contemplated as a career. He had worked for The Michigan Daily, while studying at the local university, and was a summer intern at Forbes magazine. Later, he became a trustee and benefactor of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, while being a pretty active private equity investor in media.

Wasserstein smartly sold American Lawyer Media’s 29 legal newspapers and magazines to the UK’s Incisive Media in July 2007 for $630m before the banking crash – and his company bought it back for two-thirds of the price seven years later. But he made clear that New York magazine was a different kind of investment by transferring it to the Wasserstein Family Trust from his private equity firm. And it had certainly been priced as a trophy asset.

The magazine which, in the mid-1990s, had made some $8-10m of annual profit, was down to an estimated $1m on revenues of $45m in 2002. One broker, gasping at the heady valuation, said: ”This is a publishing pet project and, if you are from New York and plugged into the scene, this acquisition provides a lifestyle fringe benefit that others don’t.” Another adviser recalled one of Wasserstein’s books which warned that ”pride or ego causes managers to launch overpriced transactions and pay steep (and unwarranted) premiums for target companies.”

Wasserstein now said that making New York magazine successful again was a straightforward, if difficult, task: ”At best, the magazine is the embodiment of New York, a very exciting city. All you have to do is be a good mirror of this city.” From the banker who had amassed a $2bn personal fortune with deals like Texaco’s takeover of Getty Oil, it was an uncharacteristically frothy comment. But he followed up the post-deal celebrations by quickly injecting enthusiasm and investment into a magazine he had read since he was a student. And, then, there was his inspired appointment of Adam Moss, from the New York Times, as his editor-in-chief.

The unexpected owner

An editor at the time described the surprising side of Wasserstein: “At monthly meetings, he fired questions, but never gave directives. For a man with such a serious reputation, he laughed a lot, a deep-throated guffaw that settled down into a cartoon-size grin. He knew the magazine would occasionally cause him trouble in his social set; secretly, he seemed to enjoy that. He’d bought the magazine as an investment but there is no denying that, for him, owning it was partly its own reward.”

Two years later, New York began an aggressive digital expansion with the relaunch of the magazine’s website and a series of blogs. The magazine was quicker than most to embrace the web as a potential source of profit. The New York Times noted: “In a way, New York magazine is fast becoming a digital enterprise with a magazine attached.” No mean credit to the direction Wasserstein was pushing his favourite magazine at a time when print was first being battered by all things digital.

But, in 2009, there was another shock: Bruce Wasserstein died suddenly, age 61, after a routine heart operation. It was just one year after the death of Clay Felker, who was 21 years older.

A New York Times’ obituary underlined Wasserstein’s impact on New York magazine in the six years since he acquired it: “While previous owners had required constant features in the magazine about the best place to get a croissant or a beret, it was clear that

Wasserstein wanted a publication that was the best place to learn about the complicated apparatus that is modern New York. In enabling as much, Mr Wasserstein recaptured the original intent of the magazine’s founder, Clay Felker.” Adam Moss described his late boss as having the “soul of a journalist and the wallet of a tycoon.”

Today, the magazine’s publisher New York Media is overseen by Wasserstein family members. Like Wasserstein himself, they’ve ploughed profits back into the operation and continued to invest. But there have been some tough decisions.

Two years ago, Moss and his team were celebrating their latest “Magazine of the Year” award for continuing achievements in print and digital. But, within six months, they announced New York would be cutting back to (sort) fortnightly frequency. Like weeklies everywhere, the loss of classified advertising had wiped out profitability.

Journalists and advertisers responded to the news with predictions about the demise of print. The New York Post (still published by Rupert Murdoch) gloated, while Time magazine was sad and pessimistic: “If New York cannot hack it as a weekly, no magazine can.” The Gawker blog said: “We were not joking when we told you thousands of times that print is dead”.

End of print?

The New York Times reported that “something palpable and intrinsically thrilling will be lost with the change in rhythm to a magazine that has been hitting the streets on a weekly basis for more than four decades. Along with the closing of the printed Newsweek <subsequently reversed> and the planned spin-off of Time Inc… the move to bi-weekly publishing represents the end of an era and underscores the dreary economics of print and its diminishing role in a future that’s already here.”

It seemed as if it was only a matter of time before shrinking print advertising finished off the printed New York. The magazine’s ad pages had declined 9% in the nine months leading up to the announcement of reduced frequency. But there was a surprise: the planned reduction from 42 to 29 issues a year would involve not a reduction but an increase in staffing as it committed to investing the $3.5m print savings into digital expansion and into 20% more pages in every issue. By the end of 2014, New York was claiming success for

“doubling down on the stuff that’s already working”, namely the digital sites. The entertainment and culture site Vulture last year increased its monthly uniques by 53% to 10.5m while beauty, fashion and relationships site The Cut jumped by 38% to 8.6m. The Daily Intelligencer politics and business site has hit 3.8m. And The Vulture Festival attracted 35,000 to its (profitable) inaugural event.

New York reported 20% growth to 12m in “total gross audience” (i.e. print and digital combined) for August 2014. And, while annual print advertising is now closer to 2,000 pages than the 3,500 pages it once reached, last year saw only a small overall decline. Suddenly, the magazine was celebrating again.

It continues to experiment with online coverage through advertiser-sponsored, limited-run or “pop-up” blogs including The Cut’s retrospective on vintage fashion, sponsored by Burberry, and the art-focused “Seen” sponsored by Chanel. In the wake of the “Serial” podcast boom, it has also started producing audio content on Slate’s Panoply network. Its first shows include “Vulture TV” and the weekly podcast “Sex Lives”.

It is 11 years since Adam Moss was lured to the magazine from the New York Times. He has been responsible for its ambitious digital expansion and much else. Early on, he transformed the NYmag web site from what was described as a “magazine companion” to provide hourly-updated, original coverage of politics, personalities, entertainment, fashion, and food.

Beyond the city

He followed up with the development of Vulture, the expansion of the Grub Street food and restaurant blog, and The Cut. Last year, he reinvented the magazine as it switched to bi-weekly with new features, more photography and visuals, a new fashion section, and columns on tech, sex and Hollywood. It is still a thrilling magazine that could yet become an international success. Which is, of course, where the web comes in. Some 80% of the magazine’s online audience is now from outside New York. It is easy to believe that its unspecified international audience could grow substantially at a time when news brands are going global.

It is six years since Bruce Wasserstein’s death and, though Moss was reported to have said “his family told us that the magazine was always meant to be owned by the family, and that it was not bought as a quick turnaround project,” there must be some sense of being in a race towards the safety of steady profitability. Even a committed family can tire of the $1-2m losses which the magazine is assumed still to be making. Advertising revenue is now 55% digital, though that apparently healthy trend has been “helped” by the decline in print. But the growth of digital revenues should reassure the Wasserstein family that the business is now worth much more even than their father paid for it. And the value is going up not down.

For all the continuing shocks in the magazine sector, New York’s print circulation has remained steady for the past five years at around 400k (90% of which is subscription). Its 2m total readership is evenly divided between men and women.

The familiar options for magazine publishers involve what one media buyer described as “trying to change the tyres while they’re doing 100mph”. They include the simple question of whether or not to use print merely as a content marketing ancillary for what becomes primarily a digital business. New York shows that – for some distinctive, high-value magazines which can keep their nerve – there really is the option of developing first-class digital media while also reinventing and reinforcing print.

Readers remain hooked on New York magazine and can become the solid, profitable core audience that some major daily newspapers might just come to appreciate – once they get used to depending on circulation rather than advertising revenue. And news stand sales (which now comprise almost 10% of the magazine’s circulation) have almost trebled during four years in which the cover price has increased by 40% to $6.99. That’s powerful encouragement.

Its owners will have cheered what Vogue supremo Anna Wintour (and, incidentally, fashion editor of New York itself in the 1980s) said last month in their own magazine: “Well, I think that it’s very important to make… print publications even more luxurious and even more special just to differentiate us from everything else that’s out there. Print publications have to be as luxurious an experience as possible. You have to feel it coming off the page. You have to see photographs and pieces that you couldn’t possibly see anywhere else.”

Wintour would, similarly, agree with the New York view that a more visual, distinctive version of print increases its appeal to the luxury and fashion categories that continue to be the most durable part of the magazine advertising business.

Innovating in print and digital

Nothing, though, is easy for magazines, a media category whose profitability has traditionally depended on advertising and the sit-back-and-enjoy habit of readers. And, even the strongest brands may be further undermined by the continued growth of free publishing. Close to home, the Village Voice and Time Out are both now free. But New York magazine impresses with the gutsiness of its strategy. It has been investing for more than a decade in sparky digital properties, has skilled-up successfully in digital ad sales and sponsorship, and has been launching profitable events. But – most distinctive of all – it is fighting harder than ever to ensure it remains an innovative leader in print. The magazine remains at the heart of an increasingly versatile media business that knows its market and really is firing on all cylinders.

As if to emphasise how New York magazine is starting to thrive in a world of digital tigers, Advertising Age made it second only to the fiery Vice in their A-List recently, saying: “New York offers a way forward for weeklies trying to reinvent for the digital age. Last year, it reduced frequency to every other week. Print ad pages were down only slightly despite fewer issues, and digital ad sales are picking up the slack, accounting for half total ad revenue. Editor-in-Chief Adam Moss deftly incorporated digital franchises into print. New York won another three National Magazine Awards last year under Mr Moss, who continues to be pitch perfect in capturing the zeitgeist in each issue.”

It’s up to you, New York.

26 April 2016 UPDATE (from New York Times):

Adam Moss, the editor in chief of New York magazine, was having dinner at Sant Ambroeus, an upscale restaurant in the West Village, with Pamela Wasserstein and her two brothers when she mentioned that she was ready for a career change. It was the summer of 2014, the magazine had just gone from weekly to biweekly, and Mr. Moss recalled thinking at the time that it made sense to have the Wasserstein heirs, whose family trust owns the publication, more involved with the day-to-day decision-making. The next day, Mr. Moss called Ms. Wasserstein, then working for the company behind the Tribeca Film Festival, and floated an idea: She should run the magazine. Nearly two years later, that plan is finally coming to fruition. On Monday, Ms. Wasserstein, 38, will become chief executive of New York Media, the magazine’s parent company, giving the family more direct control of the publication and making it something of a New York media dynasty. The move can be traced to 2004, when Ms. Wasserstein’s father, Bruce Wasserstein, bought New York magazine for $55 million. After Mr. Wasserstein, an investment banker who helped popularize the hostile takeover, died unexpectedly in 2009 at 61, there was a short period of uncertainty about the publication’s future. The economy had soured and some speculated that the family might sell. (www.nytimes.com)